10 innovations revolutionising carbon markets

In the last few years we have seen a number of innovations and developments that are changing carbon markets dramatically. The data, information and tools available to market participants are significantly different compared to a decade ago.

There remains a lot of work to be done to grow these markets to make a meaningful net zero contribution. But these innovations are laying the foundations to get us there. Below we look at the 10 that we think are having the biggest impact on raising this potential.

1. Ratings - carbon markets are learning the language of risk

Ratings are now commonplace in the voluntary carbon market. We have seen them used in every part of the value chain, plugging in at any stage in a project lifecycle to help people make better decisions. Examples include the first public ex ante rating being published earlier this year and the first ratings-linked contract being launched.

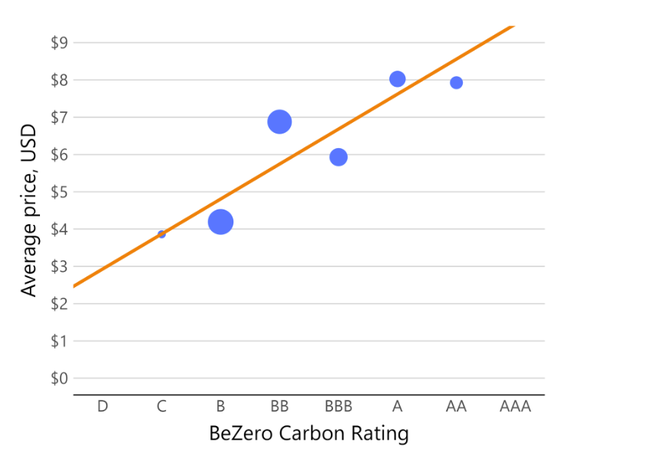

Despite the volatility in the market this year, we have seen a continued correlation between the BeZero Carbon Rating and pricing. Our analysis finds that, on average, each ratings notch (on our eight-point scale) leads to an additional 25% price premium for credits in the market. With ratings helping to shift the incentive structure in the VCM to better reward quality, projects with the greatest climate impact have the most to gain.

Figure 1. BeZero Carbon Rating versus average credit price on CBL exchange for the period April 2022 through December 2023. The number of transactions for credits of each BeZero Carbon Rating in the period analysed is indicated by the size of the data point. Plotted linear regression line calculated on the full transaction-level dataset.

2. Satellite imagery - everywhere and all the time

Satellite data and downstream analytics are increasingly targeting applications in the carbon market. Space agencies such as ESA, ISRO, JAXA, and NASA provide open data, including LiDAR and radar aimed at measuring carbon. Through initiatives such as NICFI, some commercial satellite data are also open for climate research. Combined with cloud computing and the march of machine learning, innovation is booming.

Numerous companies and open science initiatives are now competing to provide affordable satellite monitoring to project developers and independent third parties, targeting forestry and agriculture and renewable energy, through to direct measurement of GHG flows at local to jurisdictional scales. This competition will drive higher quality and lower costs for project monitoring (see number 3).

Unique in this mix is Planet Labs, whose fleet of commercial satellites maps the entire world every day. BeZero’s partnership with Planet will see their high-resolution data - alongside other data from space agencies, government institutes, and researchers in the field- used to inform independent carbon ratings for hundreds of projects globally. This constant eye on project performance makes ratings a real-time risk metric for the carbon markets.

Meanwhile, some aspects of carbon accounting defy direct observation, no matter the tech. Project baselines - the unobservable elephant in the room - have come under scrutiny this year, for instance. Solutions exist however, among them integrating the latest satellite data with dynamic baseline methodologies and independent, jurisdictional risk maps - an approach that is working its way into standards, while already routinely applied by BeZero, among other agencies. On all fronts, the data and science are supporting an increasingly rigorous and transparent market.

Figure 2. Forest structural attributes and carbon mapped for an Improved Forest Management project in Mexico, using data from Planet in partnership with BeZero.

3. Monitoring, reporting & verification (MRV) - bigger, better and more often

All carbon projects are live, but historically the availability of data on their performance has not reflected that. Monitoring was expensive and reporting cadences were in the decades in places. However, this is changing for many project types. New technologies are opening access to datasets that are more expansive, timely, accurate, and verifiable than the data that was previously available.

Not only are innovations in Earth observation data having big impacts in the forestry space, but the technology behind other project types is also changing rapidly. Cookstove projects are coming to market with data on the usage of individual cookstoves made available through the use of sensors. In agriculture, the use of low-cost probes could make tracking soil carbon more cost-effective and accurate. There is even talk of digital health sensors on cows to monitor digestive emissions or feed into pasture management.

The availability of these types of data has been influencing how accreditors think about methodological improvements, with Verra’s new jurisdictional REDD methodology incorporating the improved MRV capabilities in the market.

4. Regulators & initiatives - from theory to practice

An enormous amount of work has been done across the market to improve standards and practices. This has culminated in new principles and initiatives on both the demand and supply sides that are now set to be operationalised.

On the supply side, having published its Core Carbon Principles (CCPs), the ICVCM is set to announce which methodology types will qualify, as well as assessing applications from accreditors. This should mean that we see the first CCP labels in the market this year, raising the bar in a number of areas for what a carbon credit looks like.

On the demand side, the VCMI has published its guidance on what a credible claim looks like. Having been stuck for an alternative to the misleading precision of ‘carbon neutral’ labels, this framework will give the market more confidence in using carbon credits as part of a broader climate-based claim.

At COP28 we saw both of these initiatives come together with SBTi and the GHG Protocol to collaborate on delivering clear, cohesive standards for corporate climate action.

These progressions come at a time when a number of governments are looking at the market, be it in terms of oversight or utilisation. Many are looking at the extent to which these initiatives provide a blueprint for potential regulations. More consistency is always helpful for market participants.

However this consistency should not be achieved by treating credits like a commodity. Any regulation based on the idea that all credits are the same is destined to fail. With any luck, regulators and the initiatives will continue to push the market towards better information, data, and transparency.

We have also seen governments looking to include international credits in their national climate strategies, such as Singapore, which is making them eligible against their carbon tax. Similar consultations are underway in Japan through the GX League, and in South Korea.

5. Technological removals - rise of the machines

Nothing splits opinions amongst the carbon crowd like technological removals - climate saviour for some versus a dangerous distraction for others. While we sit firmly in the ‘everything, all at once’ camp on the macro of tackling climate change, this has largely been a theoretical debate given the lack of delivered tech removals.

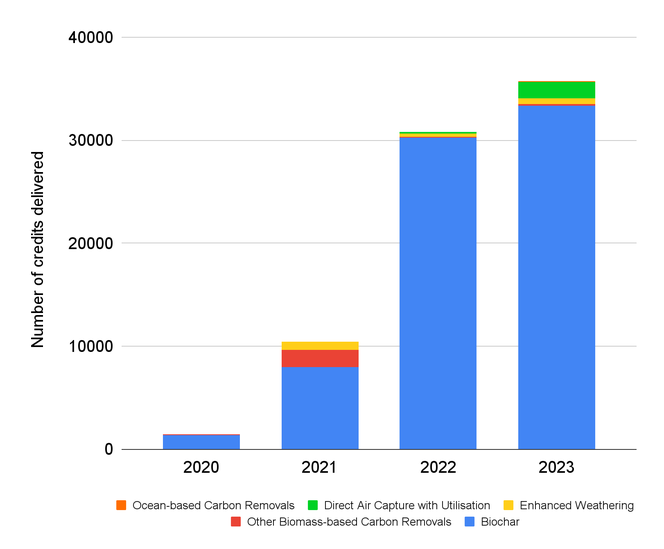

However, in the last couple of years huge strides have been made towards tech removals becoming a prominent sector of the carbon market. Total issuance for the sector was 10x larger in 2023 than it was in 2020 according to data from CDR.fyi. While the bulk of this is made up of Biochar credits, we have also seen credit issuance in Enhanced Weathering, Mineralisation, and Bio-oil.

Direct Air Capture remains nascent, but there have been notable milestones around the world. For example in Iceland, Climeworks is progressing construction of Mammoth, their second plant. In the US, ground has been broken on the Stratos plant after Carbon Engineering’s purchase by Oxy and tie up with 1Point5, while Heirloom is commencing operations on their first plant in the US. In Africa, Octavia is developing the continent’s first pilot DAC facility utilising Kenya’s geothermal power.

While the numbers remain small, the pipeline of technological removals projects continues to grow. This has been aided by new accrediting players in this space, such as Puro and Isometric, bringing new methodologies to market. Ongoing support from both the public and private sector is required if the sector is to make its way down the cost curve. This year’s large number of elections will be important to see how support for this space evolves.

As part of the sector’s integration into the market, this year saw BeZero launch the first ever Biochar rating to the market. We expect to see the first ratings for a number of other technological removals projects this year.

Figure 3. Credits delivered by technological removals between 2020 and 2023. Source: CDR.fyi

6. Unique identifiers - the yellow pages of the market

How do you know the carbon credit you have purchased is the one you were sold? How do you know the credit being retired is unique and matches the records of what has been issued? Each carbon registry has its own identification system for credits issued through their respective systems. But these do not all follow the same formula and so cannot be compared across systems. This makes transacting across the market challenging, with different processes required to validate the veracity of credits from different registries.

Enter unique identifiers. Having a unique identifier for all credits in the market that follows the same formula and is fungible across systems enables participants to avoid the cost of gathering this information themselves. It also enables them to speak the same language as their counterparts in the market, reducing the cost of transacting.

Identification systems play a crucial role in other markets by acting like a directory for the market, providing an independent third party label for a given instrument. The introduction of unique identifiers to carbon credits is a vital step to increasing the functionality of the market.

7. Insurance - giving the risk to people who want it

Who bears the biggest risks in the carbon market? Historically it has been the buyers and the investors, we would argue. The buyers have taken on most of the reputational risk, as this year has shown, while investors have taken on most of the project delivery risk. While the former still needs some work (see the section on diversification), the latter is changing.

We have seen a number of big insurance companies enter the carbon markets as well as the birth of a number of carbon-specific start ups. Companies like Kita are now insuring against delivery risk; the risk that forward-purchased carbon credits fail to be issued or delivered. Oka, meanwhile, provide cover for credits upon issuance and any reversal or invalidation risk.

The insurance sector is well positioned to take on specific risks, such as political risk, fraud, negligence, or natural catastrophes. They have decades of experience, sophisticated underwriting models, loss datasets and existing reinsurance structures to draw on. In turn, more efficient pricing and allocation of risk can help attract more risk averse capital.

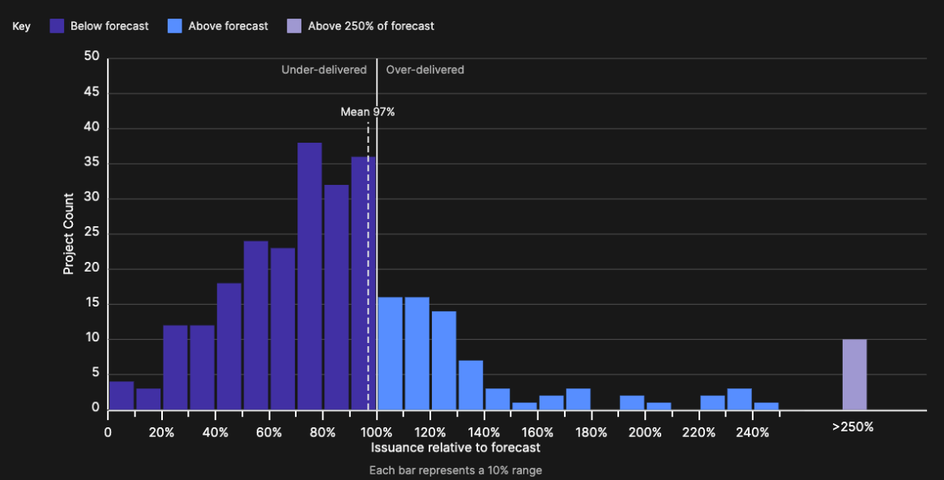

Figure 4. Data from our Issuance Risk Monitor shows that issuance can vary significantly versus what is forecast at the start of the project’s life. Insurance products can enable buyers and investors to manage their exposure to this delivery risk.

8. Diversification - buyers are tooling up

This year has shown that if the demand side of the carbon market is to scale, two problems will need to be addressed: validating the use of credits (see the initiatives section) and managing their risks. Ratings enable market participants to measure and monitor the risk, and insurance enables them to pass some of it on. But credits will always come with risks and buyers need a way to understand and manage them.

Portfolio theory can help. Historically, buyers spent lots of time doing in-depth due diligence on a small number of projects, leaving them overly exposed to those credits used to make a claim. However we have seen a growing number of companies providing portfolio solutions to clients. This enables buyers to outsource their due diligence process and access a higher number of projects than they may have available if purchasing for themselves.

Most importantly, this enables buyers to diversify the claims they make using carbon credits. With every credit exposed to risk in some form, using credits from a single project leaves the integrity of claims overly exposed to those risks. Given that these risks vary from project to project, some can be mitigated by spreading purchases across a number of projects (a topic we explored here).

9. Funding - unexcitingly innovative

Capital raised in the carbon market is estimated to have hit $6-7 billion last year.¹ This is the level it has been at for the last few years, with financial investors making up around two thirds, versus a third from corporate investors.

Underlying this headline number, we have started to see a diversification of funding sources. While their performance has been mixed, there have been a number of examples where public markets have been used to raise capital for projects now.

In terms of capital structure, we have seen some innovative debt solutions, such as the World Bank’s emission-reduction linked bond, where the coupon payments are linked to VCU issuance. We expect to see more global banks exploring how debt products and markets can play a bigger role in funding. The World Bank’s support for carbon markets at COP28 opened the door to more funding for projects.

Institutional investors globally (think pension funds and other major asset managers) are short carbon. In other words, most are invested assets that yield income flows linked to emissions. Therefore, investing in decarbonising assets that yield a return should be extremely attractive as a way to mitigate their emissions liability (see this paper by McKinsey and GIC for example).

However, they also need stable and predictable returns, something the carbon market has so far failed to deliver. The price volatility seen in the last few years and the lack of options available to mitigate this are challenging. Furthermore, most projects are in parts of the world where returns have historically been volatile given political and institutional uncertainties.

Public-private cooperation has the potential to unlock significant funding opportunities. Announcements such as the intention of the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) to enter the market could help reduce the risk faced by private investors.

10. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement - fit for use

From a carbon markets perspective, last year’s COP was disappointing. There was no agreement reached on how to move forward with some key parts of the Paris Agreement. But taking a step back, the Paris Agreement provides a national framework through which to tackle emissions and Article 6 enables market mechanisms to play a role in this. This will continue to be a key driver of carbon markets in the years to come.

Governments have the potential to be a significant source of demand in this market. While the mechanism agreed through Article 6.4 remains a way off being agreed upon and operationalised, Article 6.2 can be used today as a way for governments to fund projects and purchase credits internationally through bilateral agreements. This can be done directly by the government, or indirectly through corporates incentivised or mandated to purchase credits against a carbon liability.

The current lack of structure and process underlying the Article 6.2 mechanism makes external interrogation of these transactions even more important, and by extension the information, data and tools that enable this.

References:

¹ Extrapolating the H1 data in Trove’s ‘Investment trends and outcomes in the global carbon credit market’ report