El Niño 2023: The hot take

A moderate to strong El Niño is forecast to unfold from autumn 2023 through spring 2024. El Niño effects can cause reversal risk for nature-based solutions through increased risk of drought, fire, and flood.

We identify 61 projects across our nature-based solutions portfolio that may be exposed to elevated risk, and evaluate the likely timeline of effects.

BeZero monitors the likelihood, presence, and strength of natural non-permanence risk associated with El Niño, as well as project mitigations through risk buffer allocations.

Contents

Introduction

El Niño is a recurring climate pattern driven by changes in sea surface temperatures across the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The impacts of El Niño are not limited to the Pacific region and can have knock-on effects on weather systems across the tropics and beyond, potentially affecting many projects in the voluntary carbon market. For example, projects in certain parts of South America (west of the Andes mountain range), the southern United States, and northern Mexico may experience increased precipitation and elevated flood risk, whilst projects located in the Amazon Basin or Indonesia are likely to experience increased drought conditions accompanied by heightened fire risk. These natural risks can increase reversal and non-permanence risk for projects in the voluntary carbon market.

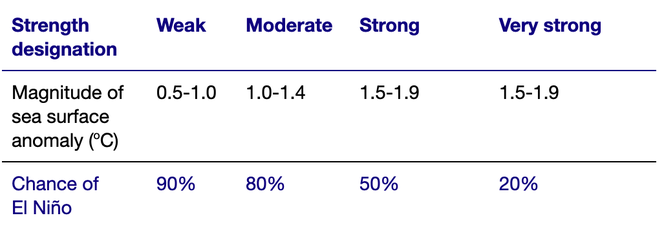

Table 1. An El Niño event is when the mean sea surface temperature in a region in the Pacific Ocean, known as the Niño 3.4 pacific region, is equal to or 0.5 degrees C above the long-term average for five consecutive three month periods. El Niño can be categorised by strength depending on the magnitude of the sea surface anomaly and below are the most recent predictions for each magnitude in 2023 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration[1], (July, 2023).

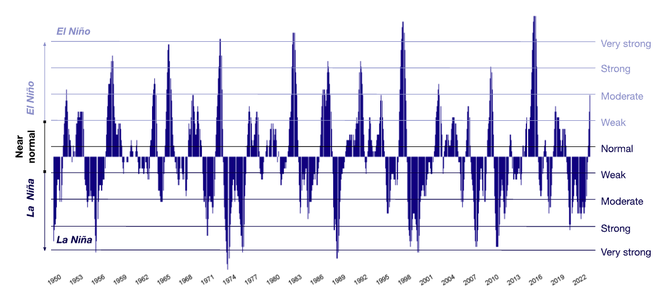

Chart 1. Historic El Niño events up until June 2023 based on data from the Oceanic Niño Index.2 In the Pacific Ocean, conditions oscillate between near normal conditions, El Niño conditions (peaks), and the inverse of El Niño conditions - La Niña (troughs). The magnitude of the deviation from normal conditions represents the strength of the El Niño or La Niña conditions which is linked to the severity and likelihood of non-permanence risk.

Forecasts indicate that not only is an El Niño event highly probable for 2023-2024, it is likely to be moderate to strong in effect.

The last strong El Niño event occurred in 2015 and resulted in widespread fires globally, impacting high carbon stock regions such as Indonesia and the Amazon Basin. The emissions caused by the 2015-2016 El Niño fires were estimated to be 1.5 billion tCO2e.3

El Niño and the BeZero universe

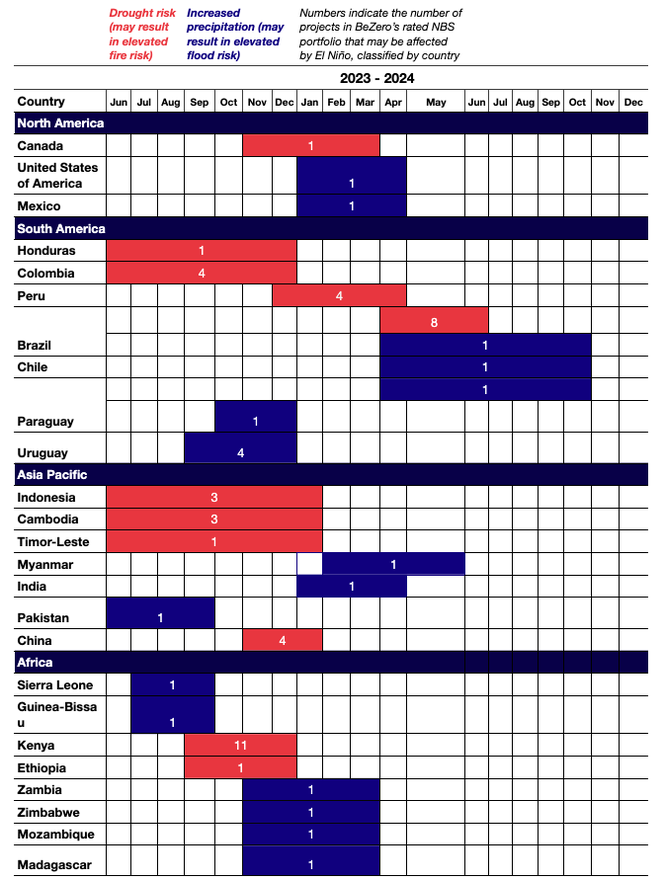

Based on global mapping of the climate modifications during El Niño events, we identify 61 projects (of 120) across our nature-based solutions portfolio which may be exposed to elevated risk.4 We find 34 of these 61 may be at increased risk of drought and, as a consequence, elevated fire risk. Meanwhile, we find 27 may be affected by increased precipitation which can result in increased flood risk (although this will vary by project).

The transcontinental nature of El Niño translates to a temporal distribution of extreme weather impacts. Based on historic trends, we can look ahead to when projects may be affected and what the risks might be.

Table 2. The potential types and temporal distribution of El Niño-driven extreme weather events in 2023 - 2024 for BeZero-rated projects across the globe (as of 30/08/2023).

El Niño, non-permanence, and buffer credits

Nature-based projects often counter the risk of reversal through the use of a buffer pool. This pooled buffer account is a reserve of non-tradable credits that serve as a communal insurance mechanism.

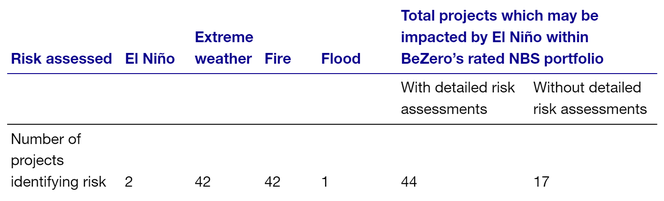

To determine the percentage of non-tradable buffer pool credits, projects may assess a variety of risks including natural, internal, and legal. We note that only 44 BeZero-rated projects (of 61 potentially impacted by El Niño) have detailed non-permanence risk assessments that consider individual natural risk components. The vast majority of these projects do not assign any risk specifically to El Niño, and typical risk buffer contributions for extreme weather, fire, and flood risk (the main impacts of El Niño) are generally less than 1% of these projects’ total issuance. This analysis indicates these risks may be under-resourced in global buffer pools.

Table 3. Only 3% (of 61 projects with updated non-permanence risk assessments) specifically evaluate El Niño risks. However, some projects with the potential for El Niño impacts do assess underlying risks such as extreme weather, fire, and floods.

El Niño events create scope for increased reversal risk for nature-based projects by increasing risk of drought, fire, and flood depending on a region's location and ecosystem type. To assess the risk presented by El Niño, we apply both regional and project-specific analysis. This approach includes active fire detection, burned area analysis, and drought monitoring, combined with external literature. These in-house metrics are calibrated to a project’s area and 10-km and 50-km buffer regions, as well as leakage belts and reference regions as applicable. Moreover, we undertake a continuous monitoring approach to our ratings that allows us to act (via our watch process) should a reversal event occur or the risk to the project change.

Conclusions

Ahead of expected El Niño impacts this year, BeZero has mapped out a timeline for nature-based projects at elevated risk of disturbance. We continue to monitor the moderate to strong forecast of the upcoming El Niño, and any associated non-permanence risk to credit quality and buffer pools.