Building integrity: Use cases for ratings in compliance carbon markets

Here are some key takeaways

The integration of carbon credits into compliance carbon markets (CCMs) could be a game changer for carbon project financing, unlocking USD 11 billion between now and 2030 if the EU and UK alone opted for this approach.

Concerns regarding the integrity of carbon credits have held back market convergence. Ratings provide an independent, project-level assessment of carbon credit quality and therefore can be used as a tool to mandate or incentivise the purchase of credits of greater carbon efficacy.

As in financial markets, ratings could be incorporated into regulatory frameworks; for example, by setting minimum rating thresholds for credits within a CCM or imposing ratings disclosure requirements.

Contents

- Around the world, compliance carbon markets are growing

- Some compliance markets incorporate carbon credits and many others are considering it

- The inclusion of carbon credits in compliance markets has significant advantages, but integrity concerns present a barrier to implementation

- Ratings should be used to ensure that carbon credits in compliance markets deliver climate impact

- Other regulatory and market developments are needed to successfully integrate carbon credits and ratings into CCMs

- Concluding remarks

Around the world, compliance carbon markets are growing

A compliance carbon market (CCM) can be defined as any policy intervention that establishes a price for greenhouse gas emissions. In doing so, emissions move from being a ‘negative externality’ to a liability that businesses must include on their balance sheets. This provides a long-term incentive for companies to invest in tackling their emissions, offering a market-based mechanism for countries to deliver climate impact and achieve their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. This approach stems from the work of economists like Ronald Coase who argued that externalities can be efficiently resolved through bargaining and negotiation between affected parties.

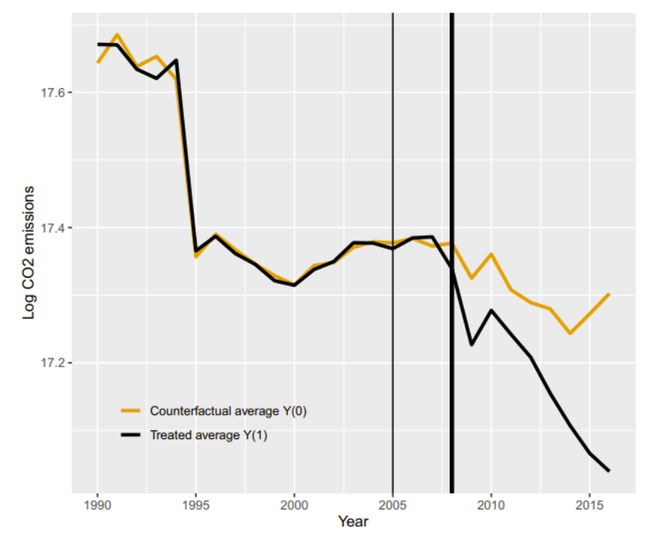

The EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), launched in 2005, was the world’s first major CCM and remains the largest globally in terms of traded volume. Numerous ex post evaluations of the EU ETS have demonstrated the success of the scheme in reducing emissions (see Figure 1 below) and this has inspired governments around the world to develop similar policy interventions. Indeed, the EU has recently announced that it will be establishing a task force to support countries that are interested in initiating similar ETS schemes.

Figure 1. Actual EU CO2 emissions from 1990 - 2016 (black line), with ETS implemented versus statistically derived counterfactual without ETS implemented (yellow line) drawn from Bayer & Aklin (2020).

The World Bank estimates that, in May 2023, 23% of global emissions were covered by CCMs. This has grown from an estimated 7% in 2012, with large jurisdictions like China, Indonesia, and the state of California having implemented schemes in the intervening years. This number is set to grow in the coming years, with the likes of India, Brazil, Thailand, and Türkiye either planning or considering a CCM.

Some compliance markets incorporate carbon credits and many others are considering it

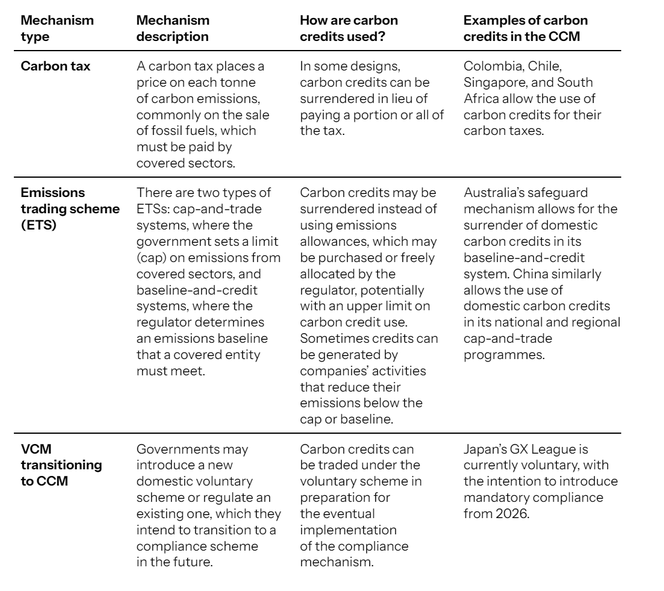

We characterise three types of CCMs, defined in Table 1 below: carbon taxes, emissions trading schemes, and voluntary markets transitioning into compliance markets. Across all of these categories, governments may choose to allow carbon credits to be used to achieve compliance under the terms of the scheme through the retirement of credits to offset emissions. This has already happened in a number of jurisdictions, exemplified in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of compliance carbon market types, with an explanation and example of how carbon credits can be used.

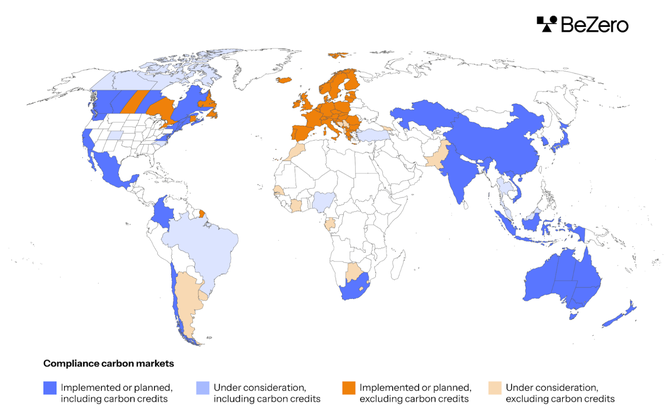

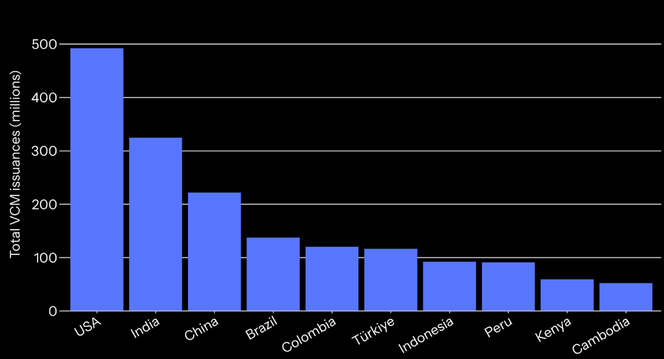

A map highlighting countries and sub-national governments by their CCM status can be found below (Figure 2). Those labelled as ‘implemented or planned’ include CCMs that are operational or have a legislated start date, whilst those labelled as ‘under consideration’ include instances where a government has announced its intention to pursue a CCM but is yet to formally legislate it. It is notable that many of the countries with the highest voluntary carbon market (VCM) credit issuance (see Figure 3) have implemented or are considering a CCM incorporating carbon credits. These countries already have a strong domestic supply of carbon credits, with the potential to scale this further to meet demand from CCMs.

Figure 2. Map displaying compliance carbon market schemes that currently or plan to include carbon credits (dark blue) or have signalled their intention to consider including carbon credits (light blue), and compliance carbon market schemes that currently or plan to exclude carbon credits (dark orange) and those that are considering implementation that exclude carbon credits (light orange). Source: adapted from World Bank, ICAP, and BeZero Carbon.

Figure 3. Top 10 countries by VCM credit issuance. Covers issuance accredited by American Carbon Registry, Cercarbono, Climate Action Reserve, Gold Standard, Puro.Earth, and Verra.

The inclusion of carbon credits in compliance markets has significant advantages, but integrity concerns present a barrier to implementation

Why are many jurisdictions opting to include carbon credits in CCMs? The key factors include:

Delivering greater climate action now - The retirement of high-quality carbon credits offers a means of delivering additional climate action beyond what is feasible within value chains, enabling compliance schemes to push for more ambitious emissions targets and supporting countries to deliver against their NDC targets.

Promoting efficiency - When integrated into compliance markets in an effective way, carbon credits can enable businesses to reduce the cost of decarbonisation, whilst also continuing to incentivise long-term investment in value chain emissions reductions.

Facilitating green finance - Carbon credits deliver much-needed financial incentives to carbon projects in nature-based sectors like forestry, blue carbon, and agriculture, as well as in emerging engineered carbon removal sectors. The integration of carbon credits into a compliance scheme can provide a boost to the development of such projects domestically and across the world.

Delivering co-benefits - Projects that generate carbon credits often deliver significant co-benefits, such as increased biodiversity, job creation, improved water quality, and poverty alleviation.

For these reasons, there are calls for more jurisdictions to integrate carbon credits into their CCMs. In recent weeks, the ‘architect of the EU’s carbon market’ has called for the bloc to allow imported carbon credits within its ETS. If the EU and UK alone opted to allow carbon credit retirements within their CCMs up to a maximum of 5% of the total emissions cap, we estimate that this could unlock an additional USD 11 billion of finance for carbon projects between 2024 and 2030. This illustrates the transformative potential that could be unleashed through the integration of carbon credits into CCMs.

Despite these clear advantages, many jurisdictions have been reluctant to integrate carbon credits into their CCMs. Fundamentally, this reluctance stems from concerns regarding the integrity of carbon credits as an asset that truly represents 1 tonne of emissions avoided or removed. In recent years, there has been significant media criticism of many carbon credit-generating projects, and through 2022 and 2023, we saw this criticism impact prices and demand within the VCM (although BeZero’s research indicates that demand growth has returned to the market in recent months).

Recent criticism of certain projects that are eligible for the Australian CCM illustrates a key risk inherent in the inclusion of carbon credits within CCMs: that some projects may fail to perform as expected, undermining the broader credibility of the CCM. Another significant risk is the ‘race to the bottom’, whereby participants in the scheme seek out the lowest quality, cheapest carbon credits to fulfil their obligations to comply; a less than ideal outcome from a climate impact point of view.

Ratings should be used to ensure that carbon credits in compliance markets deliver climate impact

Carbon ratings offer a tool that policymakers can use to tackle the underlying integrity issue that poses a risk to carbon credits as a mechanism to deliver additional climate action, promote efficiency, facilitate green finance, and deliver co-benefits within a CCM.

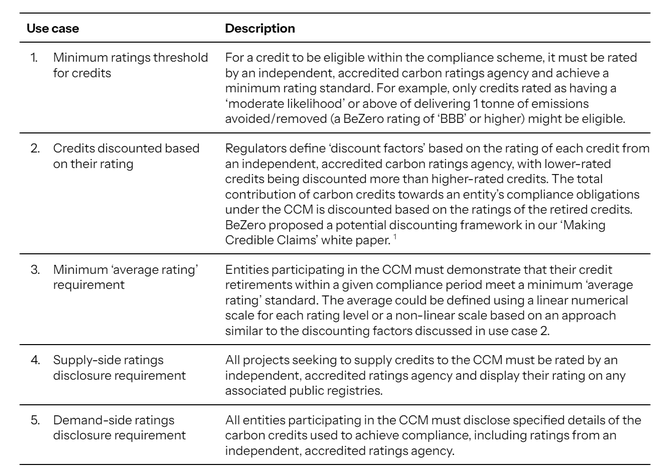

In essence, ratings provide an assessment of the efficacy of a given credit and therefore can be utilised to drive up quality standards. There are numerous ways that policymakers could consider integrating ratings into a CCM and we have put forward some use cases in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Policy use cases for carbon ratings within a compliance carbon market.

These use cases represent a form of risk management, helping to ensure that, in aggregate, the carbon credits retired under a CCM have a minimal risk of failing to deliver climate impact. This is akin to the role that credit ratings have in financial market regulation.

For instance, under Basel III regulation, credit ratings define the risk level of assets, setting the minimum liquid reserves that banks must hold and thus supporting economic stability. Similarly, pension schemes are often subject to regulatory requirements that mandate certain minimum ratings standards for the assets they hold in their investment portfolios. There are significant opportunities for CCM regulators to learn lessons from their counterparts in financial markets on the effective integration of ratings into policy.

Other regulatory and market developments are needed to successfully integrate carbon credits and ratings into CCMs

The price of carbon credits traded on the VCM is typically considerably lower than the price of emissions allowances within CCMs. Therefore, a risk to the integration of carbon credits into CCMs is that companies may be incentivised by this price mechanism to purchase carbon credits instead of decarbonising within their operations.

However, appropriate scheme design can mitigate this risk, such as placing a limit on the proportion of a compliance target that can be delivered using carbon credits. Ratings can also play an important role here, incentivising the purchase of higher quality carbon credits, the prices of which are more comparable to those of emissions allowances, and supporting the market to equilibrate at a level that continues to incentivise innovation and rapid decarbonisation.

The inclusion of carbon ratings in the regulatory framework of a CCM would necessitate the regulation of the agencies providing these ratings. This is already the case in financial markets where organisations like S&P and Moody’s are regulated by the likes of the US Securities & Exchange Commission and the European Securities and Markets Authority.

Critical to any regulation would be ensuring that agencies are independent, such that ratings are based on rigorous, well-defined technical assessments and not subject to influence from any market actors. In addition, ratings coverage would be an important consideration for regulators, since carbon ratings agencies do not currently provide ratings for all accredited carbon projects globally. Regulators may choose to tackle this issue by, for example, mandating that projects that wish to supply carbon credits to the CCM procure a rating (use case 4 in Table 2).

Concluding remarks

With CCMs and the VCM coming under increased scrutiny, the need for more advanced market infrastructure which drives up quality standards and supports greater climate action has never been clearer. Drawing on parallels from financial markets, ratings are a key tool which governments should strongly consider integrating into their regulatory frameworks.

We have proposed several use cases for ratings in CCMs that integrate carbon credits, ranging from minimum rating thresholds to lighter-touch ratings disclosure requirements. We view these proposals as being the opening gambit in an ongoing conversation we wish to have with governments and regulators globally. We firmly believe that ratings are key to tackling the integrity issues that have led to a fall in confidence in carbon markets, helping to deliver much-needed financing to critical carbon projects across the world.