What drives the lowest BeZero Carbon Rating?

Here are some key takeaways

This week we downgraded seven project ratings from ‘C’ to ‘D’, classifying them as having the ‘lowest’ likelihood of delivering a tonne of reduced or removed carbon within our rated universe.

All ‘D’ rated projects have been accredited and verified, but our independent analysis reveals clear evidence of one or more severe risks to the projects’ core claims.

Examples of what could drive a ‘D’ rating include material loss of project carbon stocks or carbon revenues that are immaterial as a share of overall revenues.

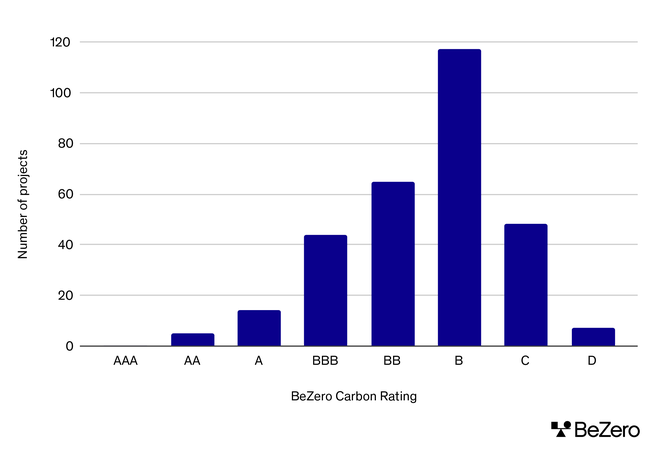

Distribution of projects by BeZero Carbon Rating (as of 24/04/2023).

It is vital for market participants to understand what factors put the quality of a carbon credit at risk, and how likely that credit is to deliver a tonne of carbon avoidance or removal. Our ratings model provides analysts with a guide on the relative weight of different risk factors, but this is not prescriptive.

Just as not all credits are equal in quality, we believe that not all individual risks are equal in their impact on credit quality. Some risks can override others, and significant risks may disproportionately drive the overall BCR. In these circumstances, where a specific risk is considered to have an outweighed impact on the overall rating, the rating can be driven by or constrained by said risk.

For a more in-depth look at the ratings process and framework, please see the BeZero Carbon Rating Methodology.

Here, we describe three examples of these risks, which result in a credit providing the lowest likelihood of achieving one tonne of carbon avoidance or removal.

1. Failure to meet the commitment period

Sub-sector: Avoided Deforestation

Risks to a project’s permanence may be overriding where we observe that a project’s credits are unlikely to maintain the carbon avoided or removed for the time committed (the project’s crediting period). For projects in the Nature Based Solutions sector group, risk of ‘reversals’ is countered through the use of a buffer pool, into which a project contributes a determined proportion of issued credits based on identified risks.

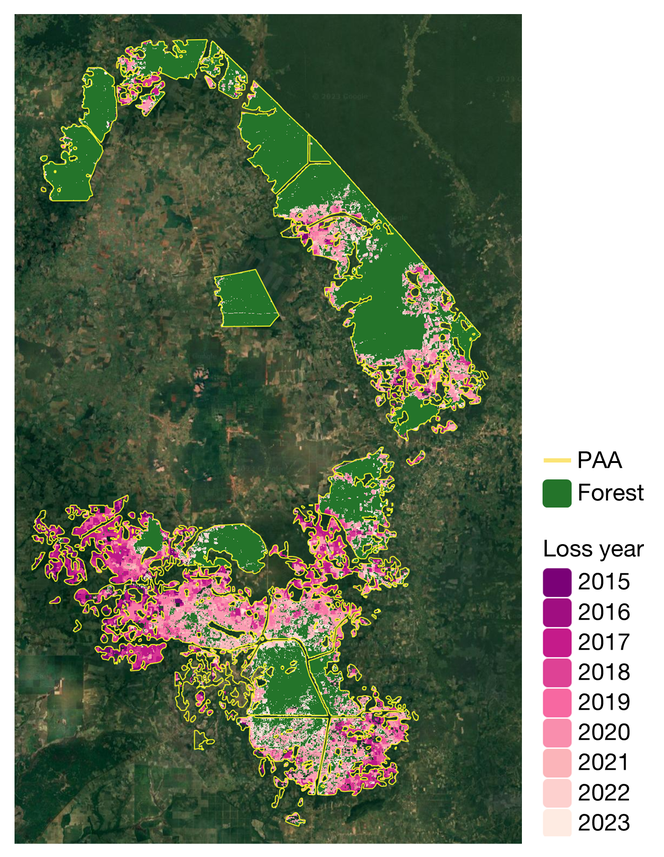

Sometimes this contribution may not be sufficient to fully cover substantial carbon stock losses. Such is the case for VCS 1689, an Avoided Deforestation project in Cambodia.

Our machine-learning models, which segment forest cover at 10-30 m resolution, indicate it is unlikely that credits of any vintage will outlast the project’s crediting period (30 years). A simple linear extrapolation of forest loss since the project start date in 2015 suggests that natural forest within the project’s accounting area could be completely cleared by around 2030. The project’s buffer pool contributions of 10% are unlikely to be sufficient to mitigate the scale of projected losses.

To date, the project has stated net emissions reductions of 723,070 tCO₂e against the project baseline between 2015 and 2019, and a total risk buffer allocation over this period of 72,305 credits. However, according to the forest loss we observe in the project area, deforestation has far exceeded the project’s baseline, and buffer credits are insufficient to cover the ongoing losses we observe. This raises significant risk to the permanence of credits issued by the project.

Forest loss mapped within the project accounting area (PAA) of VCS 1689. Between the project start in January 2015 through to March 2023, approximately 20k ha of natural forest was cleared (half of the initial extent), with loss rates increasing over time.

2. Feasibility in the absence of carbon finance

Sub-sector: Enhanced Oil Recovery

Financial additionality is a major consideration when assessing a credit's quality.

We find this to present an overarching significant risk for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) projects, due to the insignificant share of carbon finance in overall revenues. These projects inject and store carbon underground in order to extract remaining oil from previously tapped wells. As a consequence of project activities, the amount of oil extracted from a given reservoir can be greatly increased and thus provide substantial revenues.

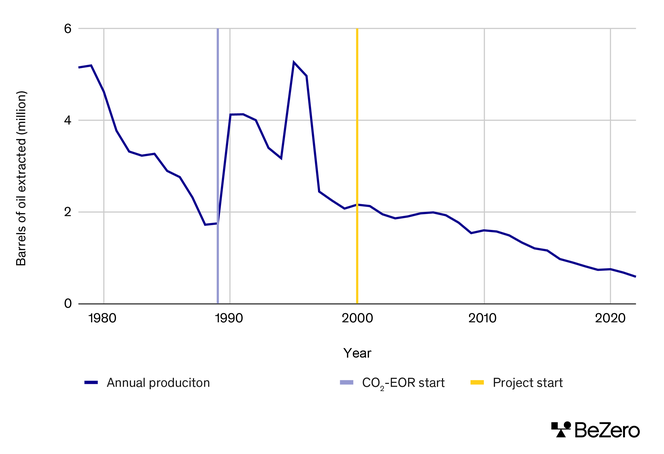

For example, we note one project in the USA, ACR117, which one peer-reviewed study found to be expected to recover an additional 42 million barrels of oil since EOR operation began in 1989, potentially generating upwards of $2 billion. Considering that the project issued 7,308,666 credits over its lifetime and assuming a credit price of $7 per tonne, carbon finance represents less than 0.1% of overall revenues from EOR activity.

Data from the Wyoming Oil and Gas Commission shows heightened oil extraction at the project site due to EOR, increasing revenues and detracting from financial additionality of the project.

Sub-sector: Other Transport

We also find carbon finance to play an insignificant role in one Industrial Processes project, GS2767. The project involves the application of advanced hull coatings to shipping vessels in order to reduce fuel consumption.

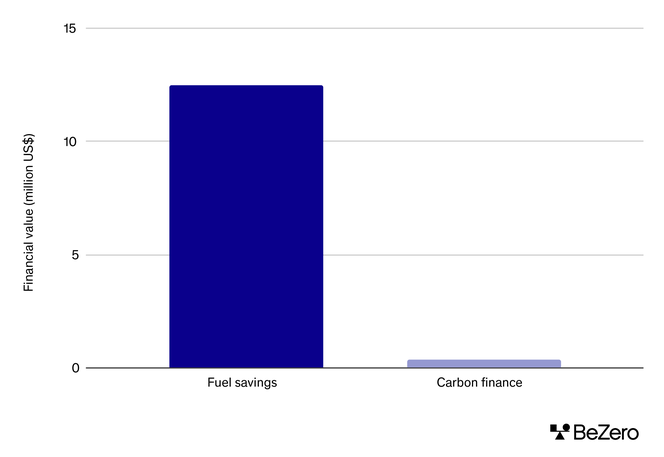

Our project-specific scenario analysis finds the financial benefit from fuel savings to the project for the period 2013 to 2016 amounts to $12.5 million, whilst total revenue from the sale of carbon credits over this period is circa $350,000. As carbon finance represents less than 3% of total potential fuel savings, it is unlikely to play a material role in the project’s successful implementation and operation.

Moreover, the project participant had shown strong intent to reduce emissions prior to the project start, investing more than $100 million in new technologies including advanced hull coatings. This intent is further evidenced by a project participant statement that more than 70% of their vessels had been treated with advanced hull coatings, whilst project documentation indicates that less than a quarter of these are included in the project.

Given that the project activity had been predominantly carried out by the project participant without the benefit of carbon finance, our view that revenues from carbon finance are inconsequential for the project are thus compounded.

Data from peer-reviewed literature and project documentation suggests insignificance of carbon finance when compared to the potential fuel savings resulting from project activity.

3. Pre-existing project activities / Methodological concerns

Sub-sector: Energy Efficiency

In some cases, a project’s application of a methodology can be the source of overarching risk to carbon efficacy.

One Energy Efficiency methodology, VM0025, designed for the reduction of on-site scope 1 stationary combustion emissions on higher education campuses, in effect requires project activities to have been occurring on the campus in the three to five years prior to project start. In order to pass additionality tests, the campus must have been reducing on-site emissions at a defined rate (a performance benchmark) in the period prior to the first year of the project.

For one USA-based project, VCS 1407, emissions reductions on the campus had already been occurring at 5.9% per year over this period. This implies that the campus has been carrying out project activities effectively independent of carbon finance, resulting in an overriding significant risk to additionality. Further, it is likely that any project using the methodology would face the same level of risk.

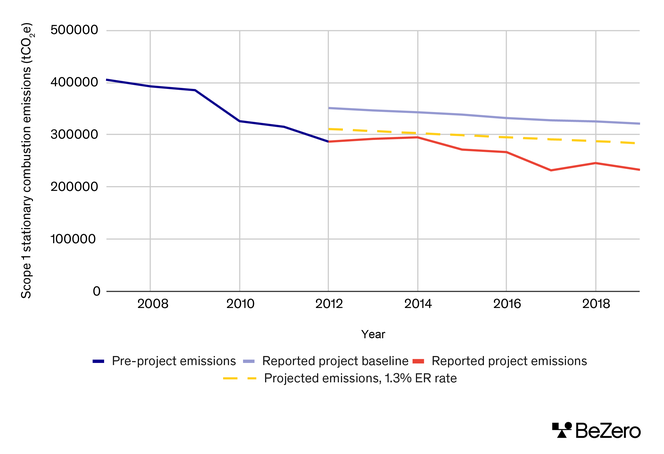

Another risk we observe which originates from the methodology is in the baseline setting. The baseline emissions for the first year of project activity are set at the average emissions over a baseline period, and for subsequent years a business-as-usual efficiency improvement factor of 1.3% is deducted. However, this approach does not consider trends in emissions reductions prior to project initiation, and likely overestimates baseline emissions.

As shown in the chart below, throughout the project’s lifetime baseline emissions consistently exceed the actual campus emissions from the year before the project started, suggesting that this baseline is likely to lead to significant risk of over-crediting. A more conservative approach would be to apply the efficiency improvement factor to the emissions of the year prior to the project start to set baseline emissions for year one of the project. Against these projected emissions, the project has significantly over-credited; by over sixfold in 2014 and by 220% in total between 2012 and 2019.

Data from the Second Nature shows reported and projected campus emissions against the project’s baseline

Conclusions

When we expanded our rating scale, we intentionally set a high bar for evidence to justify giving a project a 'D' rating. We have a duty to ensure that we do as much as we can to understand the spectrum of risks a project faces and not overly penalise how a project was implemented just because one risk factor, or piece of evidence could be used to undermine it.

BeZero’s approach is analyst-driven, model-informed and every member of the ratings team must agree that, on the balance of risk, the project’s rating fits our analysis of the evidence it provides.

This blog shows that sometimes, we do find clear evidence that a project has not chosen the most appropriate methodology, has struggled to forecast and then mark-to-market deforestation trends, or argued that marginal, at best, carbon revenues are needed for a project to be viable. Of all projects in the BeZero’s rated universe, those with the 'D' rating face the highest risks to their carbon efficacy claims.