The IUCN Peatland Carbon Code: An Avenue for VCM Expansion Into Non-tropical Peatlands

Here are some key takeaways from the blog

Non-tropical peats represent a heavily degraded form of peat that is currently underrepresented in the voluntary carbon market.

The IUCN Peatland Carbon Code is the largest Standards Body that focuses on the restoration of degraded non-tropical peatland.

Based on reported ex-ante prices, IUCN Peatland Carbon Code credits - of which the first ex-post credits are expected to be verified this June - may be some of the voluntary carbon market’s most valuable nature-based credits.

Contents

- UK Peatland degradation

- How does the code work?

- Eligibility

- Additionality

- Carbon accounting

- Challenges

- Conclusions

- References

The IUCN Peatland Carbon Code is a voluntary certification standard for UK-based carbon projects which focuses on the restoration of degraded non-tropical peatlands. The Code covers the largest number of peatland restoration projects despite not currently issuing any verified ex-post credits. These credits could be among the most valuable nature-based credits in the VCM given the reported trading price ranging between £15-25. This is relative to the average reported price of nature-based credits of £7[1]. Given the Code's premium ex-ante price tag, an understanding of quality is paramount.

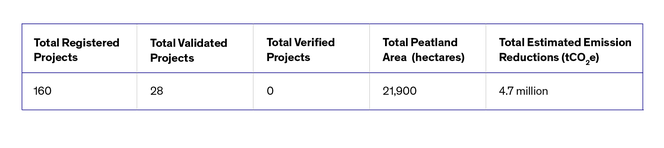

The IUCN Peatland Carbon Code’s projects as of April 2023

Given the recent release of an updated version of the Code (Version 2, March 2023) and the potential for UK peatlands to store an estimated 3.2 billion tonnes of carbon, we take an in-depth look at the Code.

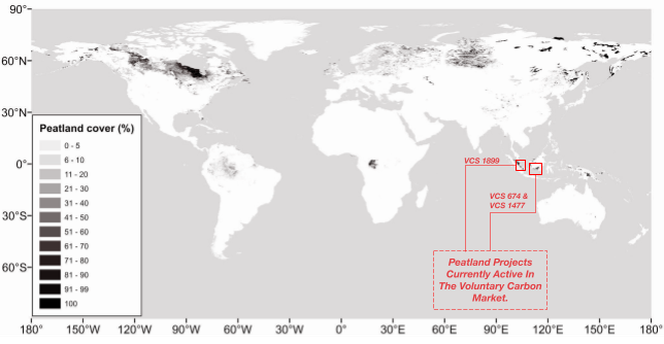

Adapted from peer-reviewed literature, this chart shows the geospatial distribution and extent (in percent) of peatlands on a global scale. We highlight the small number of peatland projects currently listed on the VCM relative to global peatland coverage [2].

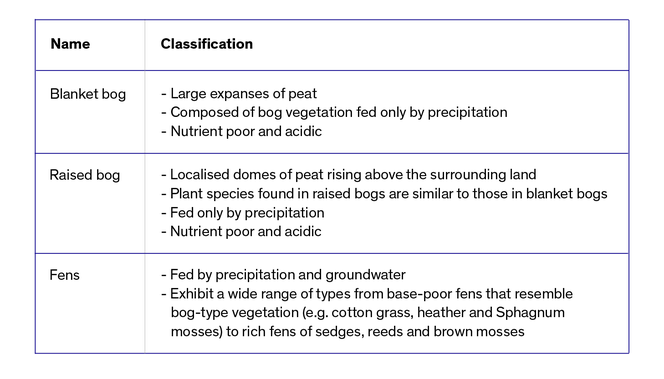

UK Peatland classification system

The UK government classifies peatlands into three main types, based on their physical and chemical characteristics:

Blanket bog

Raised bog

Fens

On the Code's original release, only bogs were considered eligible. However, with the recent release of Version 2 (March, 2023), its eligibility criteria has been expanded to include all three types of UK peatland.

Classification of UK peatlands as designated by the UK government.

A blanket bog from the Isle of Lewis, Scotland, UK [3]. The UK hosts 2.25 million hectares of blanket bog, accounting for 20% of total global blanket bog.

UK Peatland degradation

UK peatlands have been widely degraded, with 80% in a damaged and deteriorating state. This indicates scope for VCM expansion into non-tropical peatlands, and the UK could be the place to start.

Peatland degradation in the UK has predominantly been caused by land use management practices. For example, much of UK fens have been converted to agriculture, while tax incentives and afforestation schemes caused widespread loss of Scottish blanket bogs from the 1940s to the 1980s.

How does the code work?

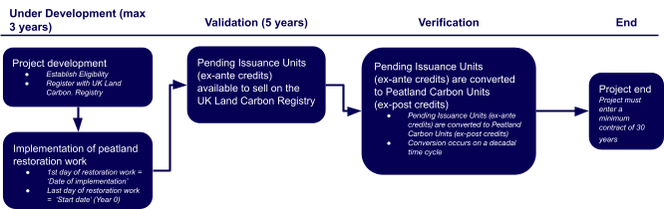

To date, the IUCN Peatland Carbon Code has been traded in ex-ante credits (Pending Issuance Units). Once a project has received validation under the Code, it is able to begin selling these ex-ante credits on the UK Land Carbon Registry. Only after the project has received verification five years after validation do these become ex-post credits (Peatland Carbon Units).

The lifecycle of a project operating under the IUCN Peatland Carbon Code.

Eligibility

Projects currently on the market (operating under Version 1) are, or were, degraded peat bogs of over 30 cm in thickness. Each project needs to demonstrate its peat depth and level of degradation through in-field peat thickness sampling, field surveys, and remote sensing. Further, projects must adhere to several other eligibility criteria including that the restoration must not be legally or contractually required, the restoration activities must not conflict with any other land management agreements, and the project must be able to enter a minimum contract of 30 years.

We view the code’s rigorous eligibility criteria (particularly those surrounding sample density) the absence of a legal/contractual requirement, and the project lifetime as likely to lower project risks.

Additionality

To effectively demonstrate credit quality, low additionality risk is fundamental. Fortunately Version 1 of the Code already had relatively stringent additionality testing and required projects to undertake four tests:

Legal Compliance - there shall be no legal requirement specifying that peatland within the project area must be restored.

Financial Feasibility - Carbon finance is required to fund at least 15% of the project’s restoration and management costs over the project duration.

Economic Alternative - Without carbon finance, the project shall not be the most economically attractive option for that area or shall not be economically viable at all.

Barriers - Barriers that prevent the implementation of the project (legal, practical, social, economic or environmental) shall have been overcome.

Whilst the number of additionality tests has been reduced in Version 2 of the Code, in our view, the level of additionality testing in both versions of the Code-in combination with the eligibility criteria- go a long way to demonstrate that these are high-integrity credits that could live up to their price tag.

Carbon accounting

Under the IUCN Peatland Carbon Code, carbon accounting is based on the peatland condition assessment and subsequent assignment of an emissions factor. The peatland condition assessment utilises a combination of field surveys, photography, and remote sensing to map out and classify areas by their level of degradation to a pre-set classification scheme. A pre-and post-restoration emissions factor is then applied by area and credits are claimed for the reduction of emissions against the pre-project conditions. The emissions factors are based on values provided by the UK Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs, and represent Tier 2 emissions factors. We consider these to be relatively robust and reliable.

In terms of monitoring, the project must produce a condition change monitoring report to maintain verification and generate ex-post credits. This occurs five years after finishing restoration and at least every 10 years thereafter for the duration of the project. Further, any immediate change or loss events must be reported in line with the Code’s risk buffer and non-permanence protocols.

Projects registered under the Code are required to apply a 10% decrease in gross emissions reductions in their carbon accounting, and restored (pristine) peatland are considered carbon neutral and not carbon absorbers. We consider these measures to be somewhat conservative, reducing the risk of over-crediting for IUCN projects.

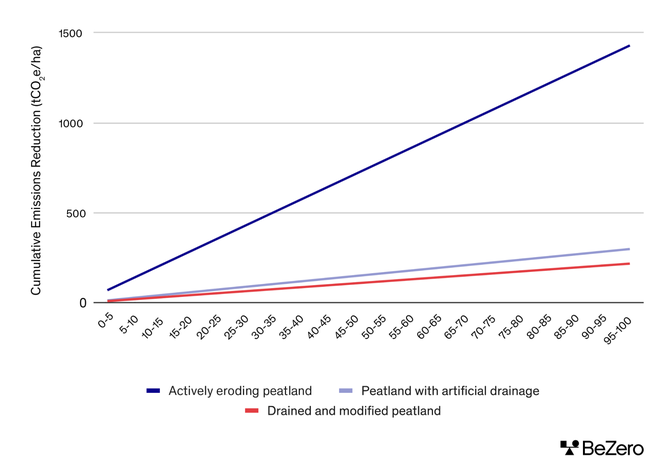

Cumulative emissions reductions from the restoration of degraded peat bogs by type under Version 2 of the IUCN Peatland Carbon Code. The Code utilises Tier 2 emission factors which are typically more accurate than Tier 1 emissions factors, as Tier 1 factors rely on more general default values. The use of empirically based, country specific emissions factors aids to increase the veracity of the carbon accounting of projects operating under the Code. Further, the Code mandates a 10% reduction to gross emissions reductions for conservativeness, further aiding to reduce risks to projects carbon accounting

Challenges

Like many developments in the VCM, the IUCN Peatland Carbon Code has encountered its challenges. A recent peer-reviewed paper sets out six of these obstacles:

Awareness: The Code launched in 2015, comparatively later than other carbon standards, so awareness is still developing.

Willingness to participate: This has been variable and has largely been dependent on historic land use practices and cultural ties.

Upfront cost: Restoration costs on peatlands can be expensive and range from a few hundred to several thousand pounds per ha.

Complexity in the application process: A case study of Code projects has alleged that application to the scheme is overly complex, especially in regards to the additionality testing of Version 1 of the Code.

Specialist knowledge: Restoration often requires specialist knowledge, equipment, and skills, all of which are currently in limited supply.

Income concerns: Land managers have outlined some concerns about ongoing income losses due to reduced productivity and/or ineligibility for agricultural support payments and tax breaks.

Despite these challenges, the number of projects lining up to register has continued to grow (Table 1). The Code has also responded to these challenges by simplifying the application process and offering specialist training to landowners and other parties to learn more about the Code and how projects can be implemented.

The possibility of raising private finance to protect or restore non-tropical peatlands is gaining traction, with several regional (sub-national) voluntary carbon markets being set up in the EU focused on the matter. These include Hiilipörssi in Finland, MoorFutures and Moorland in Germany, Valuta voor Veen in the Netherlands, and Max.moor in Switzerland. These may act as potential rivals to the Code in the future.

Conclusions

Non-tropical peatlands are currently undervalued in the VCM. The IUCN Peatland Carbon Code is the biggest Standards Body for credits of that type, and could provide the blueprint for expansion.

The implementation of the IUCN Peatland Carbon Code has faced challenges. However, with the recent release of Version 2 of the code extending its coverage to Fens, the IUCN Peatland Carbon Code now covers several types of peat that are widely observed in non-tropical regions, which could improve the applicability of the Code’s guidelines for projects outside the UK.

The strenuous eligibility criteria, additionality testing, and national datasets underpinning the Code support high integrity. But will they live up to these high ex-ante price tags? Only time will tell.

References

[1] Xpansiv’s Annual Carbon Market Review 2022

[2] Xu et al. 2018. Pub in CATENA

[3] Image attributed to Richard Webb and shared under creative commons licence