BeZero’s carbon risk factor series Policy

Here are some key takeaways

Policy risk incorporates the extent to which the national or regional policy environment relevant to a project undermines its carbon effectiveness.

BeZero assesses policy and political environment by interrogating the extent of policy support for a given project’s specific activities, including the success of implementation.

We find that activities within Energy projects and projects based in Asia generally have the highest policy risks, while Tech Solutions initiatives and projects in Africa hold the lowest.

Contents

- What is the BeZero policy risk factor?

- Components

- Information sources

- Policy Risks Across the BCR Universe

- Project-specific examples

- Conclusion

Please note that the content of this insight may contain references to our previous rating scale and associated rating definitions. You can find details of our updated rating scale, effective since March 13th 2023, here.

What is the BeZero policy risk factor?

The policy risk factor evaluates the extent to which the prevailing policy environment undermines the project’s carbon effectiveness. A carbon credit’s degree of efficacy is impacted by its local policy and political environment since a high level of support can mean that the project’s activities are already legislated for. Meanwhile, a project based in an unsupportive policy environment tends to hold higher carbon efficacy, when established in spite of a lack of government support.

This risk factor overlaps with additionally, as policy support mechanisms can partly dictate the likelihood of a project being developed. However, it warrants its own contained analysis given the multitude of other factors which are incorporated into additionality assessments. This means that it is possible for a project to benefit from supportive policies yet retain a moderate degree of additionality if it faces other technical or financial barriers. On the other hand, it’s plausible for a project contending with a lack of policy support to hold low additionality if, for example, it has alternative revenue streams and/or its activities are common practice in the region.

Within the BeZero Carbon Ratings (BCR) framework, policy receives the lowest weighting relative to other risk factors. However its pertinence is likely to increase as more governments begin to issue sovereign carbon credits, in our view.

The BCR assesses ex post credits within the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM), so our analysis of this risk factor considers only policies which are active at the beginning of a project and/or over vintage years, as opposed to expected policies.

Components

Our assessment of policy risk for a given carbon project takes into account national policies, regional policies and degree of enforcement.

1. National and regional policies

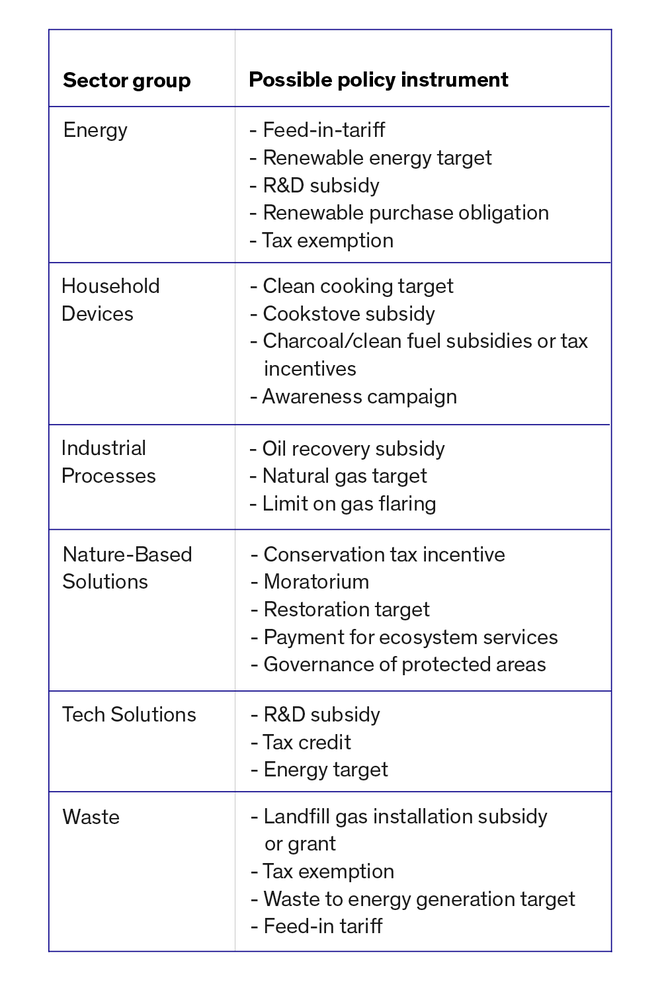

The first stage of our analytical process is to identify national policies which relate to a project’s sub-sector at the time of a project’s inception and throughout its crediting period. This includes government targets and commitments, such as those contained within Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), as well as any support mechanisms employed to achieve them such as subsidies and tax breaks. The degree of investment is also considered, where made publicly available. Table 1 outlines some of the possible policy mechanisms which can support project activities within each sector group.

Table 1: A list laying out the possible policy mechanisms across the main sector groups. Sector groups correspond to those defined in the proprietary BeZero Carbon Sector Classification System. Note this list is not exhaustive.

Next, regional level policies are identified and analysed. The prevalence and relevance of state policies varies significantly among countries and sectors, however it is important to consider how the regional policy environment interacts with national directives.

Project documentation contains material relating to the legislative environment and opportunities for receiving policy support for its activities, often via a regulatory surplus test. This test investigates the policy backdrop to a project’s activities, and requires project developers to assess whether any existing regulation requires emission reductions or removals. However, it is vital that such information is corroborated by our own top-down analysis using alternative sources, to determine the eligibility of a project’s activities for particular policy support.

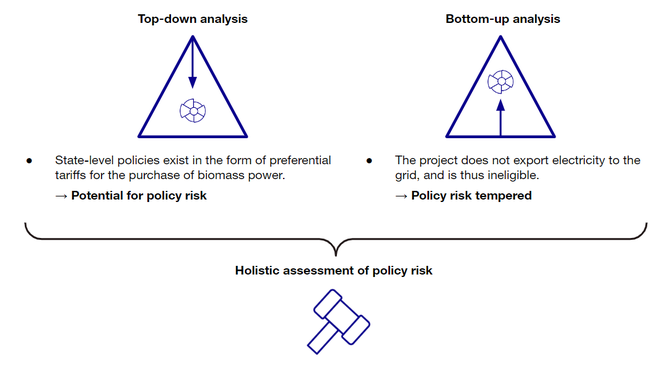

Let’s take a cogeneration power project in India as an example. The project notes several pieces of legislation which pertain to the project’s activity, but claims that it does not receive policy support. This might seem unlikely given the abundance of relevant policies in the region. However, since this project does not export electricity to the grid, it is not eligible for state-level subsidies in the form of preferential tariffs, and therefore the carbon credits issued by the project are in our view less susceptible to risks from the policy and political environment.

As illustrated in Figure 1, this top-down, bottom-up approach ensures that all potential support mechanisms are comprehensively considered and evaluated when we assess policy risk.

Figure 1: A visualisation of BeZero’s combined top-down and bottom-up approach to assessing the policy risk pertaining to the activities of a cogeneration power project in India.

2. Enforcement & Effectiveness

A crucial aspect of our assessment considers the effectiveness of policy implementation. The parameters which inform this depend on the sector to which a policy pertains. For example, assessing the extent to which feed-in-tariffs and tax exemptions successfully deliver on renewable energy targets involves determining how installed capacities of targeted technologies change after the support is introduced. Meanwhile, the success of a moratorium on deforestation can be gauged by looking at deforestation rates in the region. This evaluation of policy success is vital when determining policy risks, and demonstrates how we interrogate policy conditions beyond the mere existence of regulations stated in regulatory surplus tests.

Information sources

The sources used to inform our assessment of a given policy and political environment include government documents such as NDCs as well as key databases such as the Grantham Institute’s Climate Change Laws of the World and IEA’s policy database. To assess the degree of enforcement, we interrogate relevant peer-reviewed literature detailing fund allocations and success of implementation. This analysis can be corroborated quantitatively using the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, and helps to gauge the extent to which policy goals are achieved.

Policy Risks Across the BCR Universe

Across the VCM, the degree of policy risk depends on the extent of targeted policy support and the effectiveness of implementation. We reflect the varying degrees of risk using the following language, from highest risk to lowest risk: ‘significant risk’, ‘notable risk’, ‘some risk’, ‘little risk’, and ‘very low risk’. It should be noted that ‘very low risk’ occurs rarely.

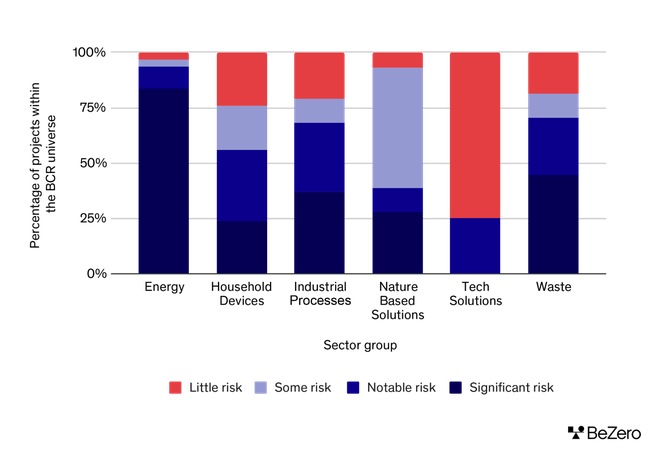

BeZero’s assessment of policy risk is influenced by country- and region-specific legislation as well as by project-specific factors. A review of policy risk across the BeZero Carbon universe of rated credits, as shown in Chart 1 below, provides some insight into how policy risk varies across sector groups. For example:

Our analysis shows that activities within Energy projects receive by far the highest degree of policy support in the absence of carbon schemes, with almost 84% of initiatives holding significant policy risks. Renewable energy technologies tend to be a cheaper decarbonisation option for governments to meet their net zero targets and thus receive the greatest level of support.

Activities within the Waste and Industrial Processes sector groups are the next most supported, with 44% and nearly 37% of such projects having significant policy risks, respectively.

At the other end of the spectrum, Tech Solutions activities receive significantly less policy support, making carbon-based interventions in our view more effective. Indeed, 75% of projects in the BeZero rated universe hold little risks, and 25% have some risks. This is perhaps unsurprising, considering the nascency of such technologies and the high associated costs.

Chart 1: BeZero’s analysis of policy risk levels by sector group shows how activities within Energy projects generally hold the highest risks, while those for Tech Solutions have the lowest.

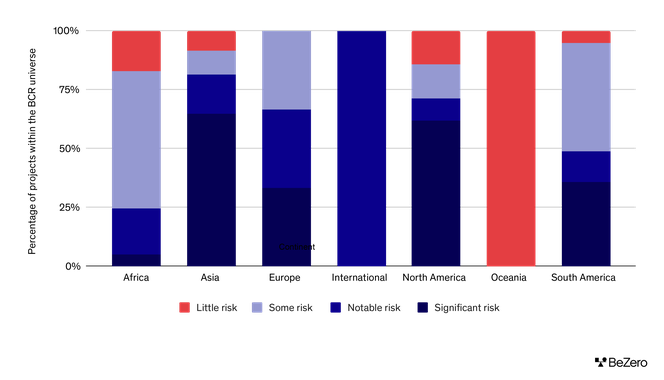

Analysing policy risk by location, we find some clear trends which are highlighted in Chart 2. These include:

Project activities on the Asian continent generally receive the most support, with nearly 65% of projects holding in our view significant policy risks. This is likely due to the high proportion of renewable energy projects based in Asia, both within the VCM and the BCR universe, and the cost competitiveness of such projects as noted above.

Activities carried out by North American projects are the next best supported in our view; almost 62% hold significant policy risks. A high proportion of projects in the USA fall under Landfill Gas and Forestry, both of which receive strong policy support from the government.

Our analysis shows that activities within African projects hold the lowest policy risks. Less than 5% of projects have significant risks, often on account of a lack of institutional capacity which in our view undermines the development and effectiveness of policy levers.

Chart 2: BeZero’s analysis of policy risks by continent reveals that activities within projects based in Asia receive the most support, while African projects receive the least.

Project-specific examples

To provide more granularity on our approach to assessing policy risks, we take a look at examples of projects which have both high and low risks across the BCR universe. The purpose of these case studies is to demonstrate how varying types of policy support and degrees of enforcement can determine risk levels.

1. Case study: Project with ‘Significant’Policy Risks

We find significant policy risks for a solar PV project based in India which started in March 2018.

We see policy risks arising from India’s 2018 National Electricity Plan, which sets a goal of 275 GW of renewables by 2027. It will increase renewable energy penetration to 44%, accounting for 24% of the electricity mix. A 33-35% reduction in the emissions intensity of India’s economy was also pledged in its Nationally Determined Contribution in 2015.

Central financial assistance for renewable energy projects is available from the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), including incentives to develop solar parks with financial assistance of up to 30% of the project cost or 50 million rupees per MW, whichever is lower. Furthermore, the Indian government’s plan to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic includes committing USD 37 billion to clean energy.

Across India, the installed capacity of solar photovoltaics has increased from 563 MW in 2011, to 49,342 MW in 2021. A similar trend is seen in all three states relevant to the project, as the capacity for all types of solar power has increased by an order of magnitude between 2016 and 2021. This suggests evidence of effective policy implementation which increases policy risks.

Each of the states in which the project occurs have targets to increase the amount of energy generated from solar, with financial incentives (including subsidies and exemptions) to facilitate the increase. This includes the Karnataka Solar Policy, which includes incentives such as exemptions from pollution board clearance and deemed conversion of land for solar projects, and in Maharashtra incentives include an exemption of electricity duty.

Altogether, this represents a highly supportive policy and political environment with strong enforcement, thus producing in our view significant policy risks for the project’s activities.

2. Case study: Project with'Little'Policy Risks

At the other end of the spectrum, our analysis of an Indonesian project which started in January 2008 and aims to prevent the conversion of peatlands holds little policy risks.

Existing policies relating to peatlands do not guarantee protection from conversion, and although a moratorium on peatland areas was introduced in 2011, we find significant evidence to suggest ineffective implementation. This leads us to conclude that threats of conversion are not significantly reduced.

In addition, the moratorium came into effect three years after the project start date and was considered only a temporary policy intervention until 2019. The project’s long-term promotion of peatland conservation would not have benefitted from a policy which had limited effectiveness, and therefore it faces in our view little risks to its carbon efficacy from a policy perspective, i.e. it is successfully operating despite unsupportive policy conditions.

Conclusion

In our view, the degree to which policy undermines a carbon project’s effectiveness is an important aspect of credit quality assessments. Although policy risk overlaps with additionality, the wide range of other factors that dictate additionality risks, such as finance and common practice, can drive disparate additionality and policy risks. Therefore, it is important to conduct a separate review of risks posed by policy and political environments.

Our analysis of policy risk considers all policies relevant to a project’s sector, as well as the eligibility of a given project’s activities for support mechanisms and the effectiveness of implementation. We incorporate information from a variety of sources, ranging from government decrees to peer-reviewed literature and public databases. These inform our view of the extent to which a project’s activities benefit from government policies throughout the project lifetime.

Despite the often broad impacts of public policy, the policy risks of each project’s activities must be analysed individually. This includes consideration of all potential sources of policy support, in addition to those explicitly mentioned in project documentation. By doing this, our assessments incorporate all available policy mechanisms in the country and region where a project is based that were operational at the time of the project’s development. This all-encompassing approach enables robust analysis of policy risks across sectors, adding an important element to the BCR framework with a view to promoting fungibility within the VCM.

Analysis of the policy risks faced by projects in the BeZero Carbon universe shows clear patterns in the risks faced across sector groups and geographic regions. As governments continue to develop new policy instruments to encourage decarbonisation, and especially as nations wade into the VCM with sovereign carbon credits, those patterns are likely to continue to evolve. A robust analysis of policy risk, as is conducted by BeZero for each rated project, will be key to understanding the risks faced by both individual carbon credits and by broader categories of credits in the years and decades to come.